In my final piece of commentary regarding Veronica Ray’s talk on “Real World Mocking in Swift” I wanted to chime in with agreement on her claim that you should write small mocks. Create mocks that “should be relatively short and don’t contain tons of info that you don’t need.”

Why You Should Write Small Mocks

Writing mocks, or any kind of test double, can become tedious. There’s certainly been times when writing my unit tests and manual mocks in Swift that I’ve started to feel dragged down by how much required code I had to write just to repeatedly create the mocks, for test after test… Of course you can factor your code nicely to reduce redundant code, but you’ll find that the need for subtle differences in your mocks can lead to a lot of code!

Or just copy and paste mocks from test to test, it’s only tests right, JUST KIDDING!

Another reason why you should keep your mocks as lean as possible, is that they often mirror your production code. One of the main benefits of high test coverage is that it enables confident refactoring. If you are writing extensive and complicated mocks that do a ton of things, chances are, you are tightly coupling your mocks with your production code in a way that inhibits quick refactoring.

A Real World Example – Mocking UIViewControllerTransitionCoordinator

I was working on some code where I needed to override willTransitionToTraitCollection in a UIViewController. I was basically adding a single line of code in the method to reposition a view’s frame when Auto Layout had finished its calculations after a trait collection transition. Simple enough. Here’s the code

override func willTransitionToTraitCollection(newCollection: UITraitCollection, withTransitionCoordinator coordinator: UIViewControllerTransitionCoordinator) {

coordinator.animateAlongsideTransition(nil) { (context) in

self.playerLayer!.frame = CGRect(x: self.videoView.bounds.origin.x, y: self.videoView.bounds.origin.y, width: self.videoView.bounds.size.width, height: self.videoView.bounds.size.height)

}

}

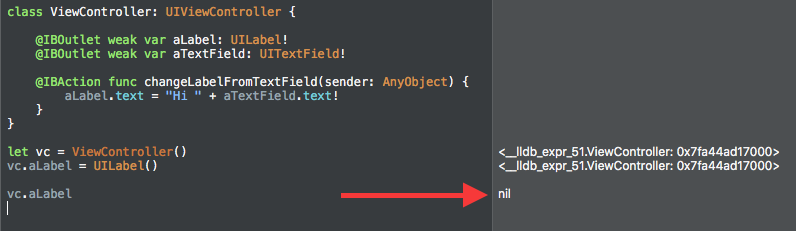

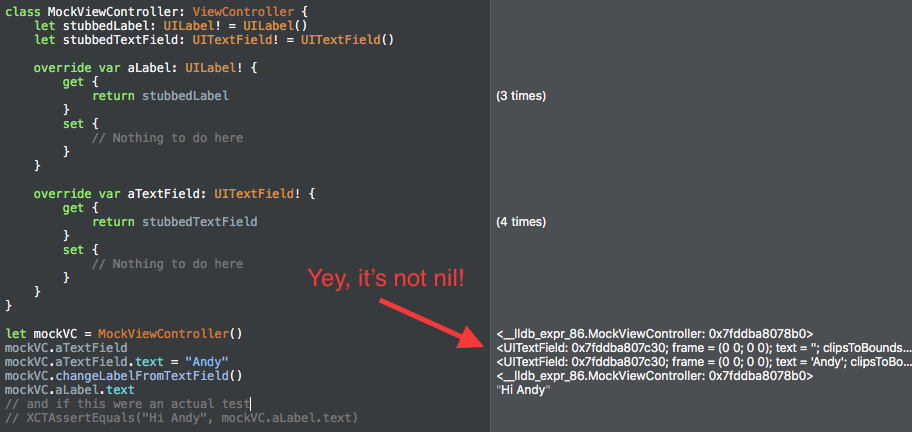

I wanted to write a unit test to ensure that coordinator was told to animateAlongsideTransition. The only way I could think of to do this was to mock out coordinator which is a UIViewControllerTransitionCoordinator and set an expectation that animateAlongsideTransition would be called.

I set out to create a mock UIViewControllerTransitionCoordinator. It’s protocol with three methods. One of those three will be the “expected” method, and the other two will be no-ops. That’s well within my loose guidelines of a “small mock.” I started out with this:

class MockUIViewControllerTransitionCoordinator: UIViewControllerTransitionCoordinator {

var animatedCalled = false

@objc func animateAlongsideTransition(animation: ((UIViewControllerTransitionCoordinatorContext) -> Void)?, completion: ((UIViewControllerTransitionCoordinatorContext) -> Void)?) -> Bool {

animatedCalled = true

}

@objc func animateAlongsideTransitionInView(view: UIView?, animation: ((UIViewControllerTransitionCoordinatorContext) -> Void)?, completion: ((UIViewControllerTransitionCoordinatorContext) -> Void)?) -> Bool {

// NO OP - don't need this method, but I need to return something

return false

}

@objc func notifyWhenInteractionEndsUsingBlock(handler: (UIViewControllerTransitionCoordinatorContext) -> Void) {

// NO OP - don't need this method

}

}

I thought this would compile, until I learned that UIViewControllerTransitionCoordinator extends UIViewControllerTransitionCoordinatorContext which conforms to NSObjectProtocol… Uh oh. NSObjectProtocol requires 14 methods to be implemented, 14 methods!!! I would have to create implementations of 14 methods just to get my mock to work, and that’s on top of the 3 methods I already had to override for the basic UIViewControllerTransitionCoordinator behavior.

I don’t really have any hard and fast rules as to how many empty methods are too many when mocking something out, but creating at least 16 empty methods just for a mock seems overkill to me, just to verify a single line of code.

In the end, I decided against mocking out UIViewControllerTransitionCoordinator and decided against writing the test. Ya, I’m not going to hit 100% coverage with this project. I’m also not going to have this really wacky, mostly empty mock sitting in my test. It’s a tradeoff I need to live with.

Happy cleaning!